I’ve been taking advantage of the mobile nature of podcasts lately (earbuds in, phone in my back pocket) in keeping up to date on accessibility trends and strategies (especially those related to AI) and, in general, what folks are doing to move their accessibility journeys forward.

One of my favorite podcasts (for a long time) is CHAX Chat Accessibility Podcast, with Chad Chilius and Dax Castro. They cover document accessibility, which I find very interesting (it's a lot more technical than I initially thought), along with trends, best practices, and even the best tools for doing the best work. These two gentlemen have a great way of making some of the more complex aspects of document accessibility and remediation a little easier to understand.

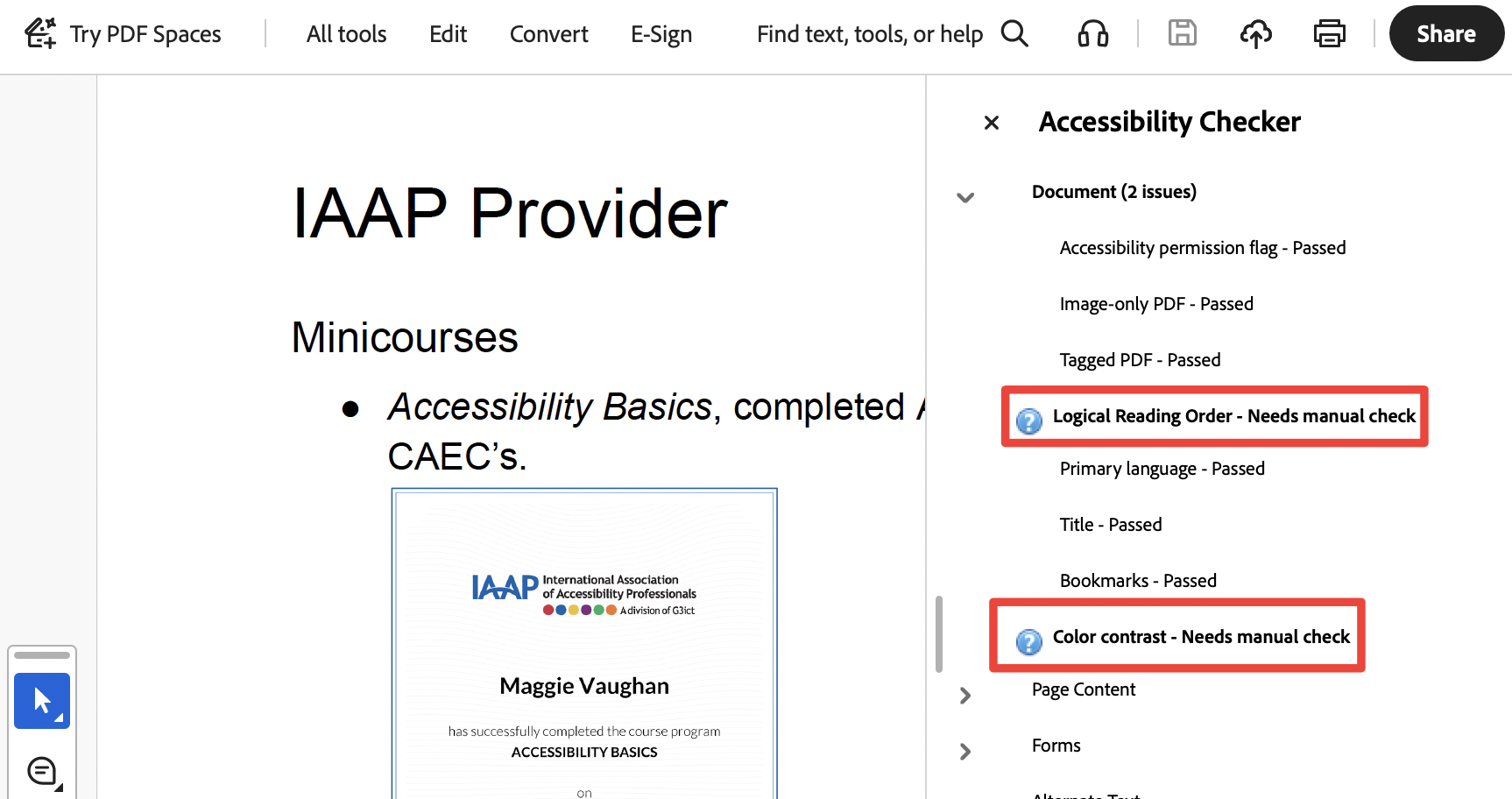

I recently listened to their podcast titled 7 things that Fail Accessibility but will pass your Checker on their YouTube channel. I fully expected color contrast and reading order to be on the agenda. Those are standard accessibility checks that an automated tool can't perform. If you run an accessibility check on a PDF in Adobe Acrobat, you always see those two checks flagged and prompting you to do a manual check.

What I wasn’t expecting to be on this list of seven is <p>, tables, and ALT text. Those issues caught me a bit off guard. I’ve always focused on the tags tree and reading order. I’d never really considered it through this other lens before, and it’s a humbling reminder that even familiar territory can still teach you something new. Thanks, guys!

For this post, I took the original list of seven, mapped each item to its corresponding WCAG criterion (with helpful head-starts from Chad and Dax on a couple of them), and highlighted how each violation impacts people with disabilities.

My goal is to reinforce the inspiration for this particular podcast: just because a checker does not flag accessibility issues does not mean your documents are compliant . And it certainly doesn’t guarantee an equal user experience for people with disabilities.

So, take a look at what your checkers can miss and how something that may appear to be a minor issue can have such an immediate impact on people with disabilities.

| What the Checker Missed | WCAG Criterion | Impact on People with Disabilities |

| P-Tags for Structure: Using paragraph tags for content such as headings or lists prevents assistive technology from recognizing the document structure. | SC 1.3.1: Info and Relationships (Level A) Information, structure, and relationships conveyed through presentation can be programmatically determined or are available in text. | Content may look fine visually, but is functionally inaccessible. The results are an inequitable access. Users with disabilities can’t access or interact with the same information as sighted or non-disabled users. |

| Layout Tables: Using tables to control visual layout (e.g., multiple columns) can disrupt the logical reading order, with user navigation flowing left-to-right rather than the intended top-to-bottom. | SC 1.3.2: Meaningful Sequence (Level A) Ensures the table's content has a logical reading order so assistive technology users can follow the data correctly. | If the sequence isn’t meaningful, the page loses its narrative and functional flow, and people who depend on assistive technology or predictable structures can’t access or interact with content efficiently, or at all. |

| Use of Color: Relying solely on color to convey meaning, such as red for high priority , fails users who cannot perceive color, even if contrast ratios are sufficient. | SC 1.4.1: Use of Color (Level A) Color is not used as the only visual means of conveying information, indicating an action, prompting a response, or distinguishing a visual element. | If color is the only way to convey information, like errors in a form or important information in a chart, people who can't see that color can miss critical information, experience confusion, misinterpret it, and incur increased cognitive load. |

| Content Order: The visual order of a document may differ from its underlying tag structure. For example, improperly anchored graphics may be dumped at the end of the tag tree, causing the reading order to be disjointed even if the visual layout looks correct. | SC 1.3.2: Meaningful Sequence (Level A) Ensures the table's content has a logical reading order so assistive technology users can follow the data correctly. | If the sequence isn’t meaningful, the page loses its narrative and functional flow, and people who depend on assistive technology or predictable structures can’t access or interact with content efficiently, or at all. |

| Insufficient Alt-Text: Checkers only verify the presence of alternative text, not its quality. Vague descriptions like line graph or 5 characters are technically compliant but offer no meaningful information to the user. | SC 1.1.1: Non-text Content (Level A) All non-text content presented to the user has a text alternative that serves the same purpose, except for the situations listed below. | Screen reader users or anyone who can’t access the content in its original form might completely miss critical info or functionality, making the experience unequal or confusing. |

| Decorative Items with ALT Text: If an image does not add value, clarity, or meaning to its surrounding content, it is considered decorative and should not receive ALT text. | SC 1.3.2: Meaningful Sequence (Level A) Ensures the table's content has a logical reading order so assistive technology users can follow the data correctly. | If the sequence isn’t meaningful, the page loses its narrative and functional flow, and people who depend on assistive technology or predictable structures can’t access or interact with content efficiently, or at all. |

| Irregular Tables: Where one or more of their headers span multiple columns or rows. They may pass structural checks, but will fail reading order. | SC 1.3.2: Meaningful Sequence (Level A) Ensures the table's content has a logical reading order so assistive technology users can follow the data correctly. | If the sequence isn’t meaningful, the page loses its narrative and functional flow, and people who depend on assistive technology or predictable structures can’t access or interact with content efficiently, or at all. |

Remember: While automated tools, like DubBot, quickly check PDFs for accessibility issues, a comprehensive accessibility evaluation also includes manual testing.

A human author creates the DubBlog posts. The AI tools Gemini and ChatGPT are sometimes used to brainstorm subject ideas, generate blog post outlines, and rephrase certain portions of the content. Our marketing team carefully reviews all final drafts for accuracy and authenticity. The opinions and perspectives expressed remain the sole responsibility of the human author.